Greenleaf Regulatory Landscape Series

The Agriculture Improvement Act of 20181 (the 2018 Farm Bill) removed hemp from the definition of marijuana under the Controlled Substances Act2 (CSA). The 2018 Farm Bill defined hemp as cannabis (Cannabis sativa L.), and its derivatives, containing no more than 0.3%, on a dry-weight basis, of the psychoactive compound delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC). Hemp derivatives include cannabidiol (CBD), as well as a range of other cannabinoids. While the 2018 Farm Bill changed the legal status of hemp for purposes of cultivation, it did not change the Food and Drug Administration’s (FDA) authority, under the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (the FD&C Act) and Section 351 of the Public Health Service Act, over FDA-regulated products (i.e., drugs, devices, dietary supplements, food, cosmetics, and veterinary products) that contain hemp derivatives.3 The FD&C Act still considers a cannabis product (hemp-derived or otherwise) to be a drug when it is intended for use in the diagnosis, cure, mitigation, treatment, or prevention of disease, or is an article (other than food) intended to affect the structure or function of the body. Therefore, since a new drug must be approved by the FDA for its intended use, with the exceptions of investigational new drugs (INDs) and cosmetic products, most products containing CBD and other cannabinoids that are on the market today are in violation of the FD&C Act.

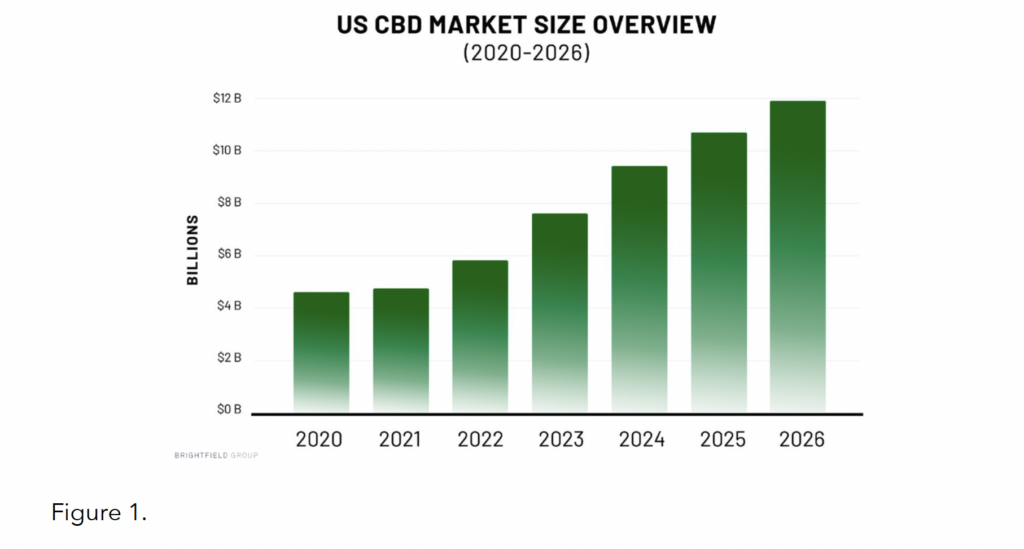

Exploding CBD Market

Since 2018, the national CBD market has exploded in size, diversity, and value – it is currently estimated to be worth close to $6 billion, with projections continuing upward over the next several years (see Figure 1).4

This market explosion has meant that consumers today have access to a wide variety of product types, including tinctures, dabs, capsules, topicals, vape oils/cartridges, combustibles, edibles, and pet products, along with an increasingly diverse set of alternative cannabinoids and substances (e.g., CBN, CBG, delta-8 THC, THC-0 acetate, etc.). Additionally, these products are being used to treat a growing number of self reported conditions, such as pain, anxiety, insomnia, stress, inflammation, and more.5

Statutory Preclusion of CBD in Foods and Dietary Supplements

Despite the prominence and continued growth of the CBD industry, the FDA has maintained that statutory barriers prevent the marketing of CBD in dietary supplements and conventional food.6 The FD&C Act §201(ff)(3)(B) (known as the “Exclusion Clause”) and §301(II) (the food prohibition) exclude CBD from inclusion in dietary supplements and food, respectively. This is because CBD is the active ingredient in an FDA-approved drug, called Epidiolex, which, through the drug’s development and approval process, subjected CBD to substantial clinical investigations prior to the market availability of CBD-containing dietary supplements and food.7 The FDA has the authority to issue enforcement discretion and carve out CBD from these statutory preclusions through notice-and-comment. However, due to toxicity concerns observed in the Epidiolex clinical trials, and with the ubiquity of CBD on the market today, the agency is reticent to green light these products until their ingredients can be shown to meet safety standards required for new dietary ingredients (NDI) and food additives per the FD&C Act.

This position was made clear in July 2021, when the FDA rejected NDI notices submitted by two CBD companies, namely Charlotte’s Web and Irwin Naturals, for their full-spectrum hemp extract ingredients.8 In their NDI notices, the companies argued that full-spectrum hemp extract is not the highly purified CBD isolate that was investigated in the Epidiolex clinical trials, and therefore, is not a pharmaceutical ingredient that would otherwise be excluded from the definition of dietary supplements. The FDA disagreed, but also indicated that even if CBD was not excluded from the dietary supplement market, per §201(ff)(3)(B), safety evidence provided by the companies did not substantiate an NDI approval. Specifically, the agency took issue with the companies’ reliance on deficient categories of evidence, deficient and/or vague evidence of the ingredient’s history of use, unreliable studies, and studies that did not adequately address reported toxicity endpoints of the ingredient (e.g., hepatoxicity and reproductive toxicity).9 In order for companies to receive an NDI approval for CBD, the FDA would need to see clinical data on particular use scenarios, such as chronic use of exaggerated doses of CBD, in order to alleviate the toxicity concerns it has with broad, cumulative use of CBD products already available to consumers.

Meeting Research Needs

The FDA, for its part, has acknowledged a lack of understanding about everyday CBD use that could better inform the toxicological impact of such products.10 Since the market took off in 2018, the agency has engaged in a sweeping data gathering initiative to fill its knowledge gaps and inform a potential regulatory framework for cannabis-derived products (CDPs).11 This work has involved conducting analytical sampling studies, gathering information on the market landscape and CDP usage, initiating FDA-led toxicological studies, monitoring adverse event reports collected through local and national portals, reviewing scientific literature, working with established external research partners, and performing post-market studies as part of ongoing drug development.12

Additionally, in late 2021, the FDA issued the Cannabis-Derived Products Data Acceleration Plan (DAP) to outline areas of research focus and remaining research needs.13 Overall, the goal of the DAP is to identify safety vulnerabilities, both current and emerging, across the CDP market. In addition to housing ongoing toxicological clinical research (assessing endpoints such as male reproductive toxicity, neurotoxicity, pharmacokinetics, transdermal exposure, etc.) and leveraging novel data sources and advanced data analytics, the FDA will look to forge internal and external government data-generating partnerships to further inform policy development in this space.14

Narrow Enforcement Activity Places Industry in a Conundrum

While it has refrained, for now, from establishing a broader regulatory framework, the FDA has persistently taken targeted enforcement action against CDPs that pose the greatest risk to public health.15 These activities have primarily involved issuing warning letters, in addition to posting consumer updates on its website. Products that have been the subject of such enforcement activities include those marketed to treat or cure serious diseases (e.g., Alzheimer’s, cancer, and COVID-19), those marketed to vulnerable populations (e.g., minors, elders, and pregnant/lactating people), and those with concerning routes of administration (e.g., nasal, ophthalmic, and inhalation).16 The agency has also called out firms marketing CDPs for food producing animals and food for humans and pets (with an emphasis on food products marketed to minors).17 Additionally, the FDA has raised quality and legal concerns related to the synthesis of delta-8 THC.18

This ‘de facto’ enforcement discretion policy, one that only targets what the agency perceives as the biggest threats to the public, has meant that essentially all CBD products on the market today are able to remain there uncontested, despite their violative legal status. In fact, even the firms that have received administrative actions have not removed their products from the market. This has created somewhat of a conundrum for both industry and the agency, where responsible CDP manufacturers feel disincentivized to engage in lengthy and expensive clinical research in order to clear NDI safety hurdles for their high-demand products, while the agency has refused to take a harder line on market participants as a whole until such clinical data is made available. In the meantime, however, the FDA has not subsided in emphasizing that GMP compliance and the presence of mature quality systems at any FDA-regulated manufacturing facility, especially those disseminating CDPs, are critical.

Changing Tides: 2023 & Beyond

Since 2019, an intra-agency work group (now titled the Cannabis Products Council (CPC)) has explored potential pathways for lawfully marketing CBD products and sought to develop FDA’s broader cannabis policy and enforcement strategy. In January 2023, FDA Principal Deputy Commissioner Janet Woodcock, as chair of the CPC, announced the agency’s determination that existing pathways for approval are inappropriate for CBD, given safety concerns, along with its intent to work with Congress to create a new pathway.19 Within this statement, Woodcock explained that “a new regulatory pathway for CBD is needed that balances individuals’ desire for access to CBD products with the regulatory oversight needed to manage risks.” Legislation providing for such a pathway could include the establishment of a dedicated Center for Cannabis, not unlike the undertakings of the Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act in 2009. Following this announcement, the FDA will coordinate with members of Congress to draft legislation while continuing to monitor the marketplace and take enforcement actions where appropriate.

Separate from the FDA’s CBD regulatory policy, recent events have furthered the potential for a new era of federal marijuana policy more broadly. In October 2022, President Biden called for the initiation of administrative processes to review how marijuana (currently a Schedule 1 controlled substance) is scheduled under federal law, while simultaneously granting mass pardons for federal convictions of marijuana possession.20 Then, in November 2022, President Biden signed the bipartisan Medical Marijuana and Cannabidiol Research Expansion Act to advance scientific research into cannabis by easing federal restrictions.21

Federal marijuana descheduling and/or broader policy reform would open doors for consumer products that contain non-hemp-derived THC or that do not meet the 0.3% THC threshold, implicating other regulatory considerations beyond the FDA. Per the 2018 Farm Bill, the FDA only contemplates what to do with products containing hemp-derived THC below 0.3% limits that are meant for non-recreational use purposes (i.e., products that make disease claims or structure/function claims). However, for products that contain non-hemp-derived THC and/or that exceed the 0.3% THCl limit, different rules will apply. For example, high-THC products that are intended to achieve a psychoactive effect will likely be treated in a similar fashion as alcohol and/or tobacco, which means very strict federal limits on toxicity will apply. These products (i.e., those with >.0.3% THC) will likely fall outside of the FDA’s jurisdiction and could be regulated by multiple other federal agencies (as is done for alcoholic beverages). With these changing tides, it’s also worth noting that federal regulatory reform has the potential to upend already well-established state frameworks for regulating everything from CDPs to medical marijuana to adult use/recreational marijuana. Existing state standards for CDP testing, labeling, dosing, and the like could also serve as models for future federal policies.

Conclusion

As the FDA works with Congress to develop a cross-agency strategy for federal cannabis regulation, they will also continue to monitor the market for bad actors and products that pose risks to humans and animals alike. This is especially the case due to recent negative public health research citing significant uptick in pediatric edible cannabis exposure and acute toxicity cases reported from 2017 through 2021,22 as well as the growing market for cannabinoids with psychoactive effects (e.g., delta-8 THC and THC-0 acetate). Since the passage of the 2018 Farm Bill, the FDA has sought to better understand the toxicological impact of CDP use by the public at large, while proposed congressional legislation, state and local legalizations, and other federal research and policy development efforts have all begun to imagine what an end to federal prohibition will look like from a regulatory standpoint. Unending policy questions remain before a regulatory framework is up and running – to name a few, upper THC toxicity limits and dosing, testing requirements and quality standards, packaging and labeling requirements, and tools for measuring impairment all still need to be worked out. However, as cannabis markets continue to point towards a strong future, regulators, and the FDA in particular, will be preparing to meet the evolution of these products head on in order to protect and promote public health.

1. PL 115-334 (December 2018), available at https://www.congress.gov/115/plaws/publ334/PLAW-115publ334.pdf.

2. 21 U.S.C. §801 et seq.

3. See Statement from FDA Commissioner Scott Gottlieb, M.D., on passage of the 2018 Farm Bill and the agency’s regulation of products containing cannabis and cannabis-derived compounds, (December 2018), available at https://www.fda.gov/newsevents/press-announcements/statement-fda-commissioner-scott-gottlieb-md-signing-agriculture-improvement-act-and-agencys

4. See Council for Federal Cannabis Regulation webinar, Janet Woodcock, M.D., Patrick Cournoyer, Ph.D., “Understanding FDA’s Approach to Cannabis Science, Policy, and Regulation” (October 2022).

5. Id.

6. See FDA Regulatory Resource, “FDA Regulation of Dietary Supplement & Conventional Food Products Containing Cannabis and Cannabis-Derived Compounds,” (updated January 2021), available at https://www.fda.gov/media/131878/download.

7. See FDA Webpage, “FDA Regulation of Cannabis and Cannabis-Derived Products, Including Cannabidiol (CBD),” (updated January 2021) (Question 9), available at https://www.fda.gov/news-events/public-health-focus/fda-regulation-cannabis-and-cannabis-derived-products-including-cannabidiol-cbd#dietarysupplements.

8. Letter from Cara Welch, Ph.D., Acting Director, Office of Dietary Supplement Programs, CFSAN, to Tim Orr, Charlotte’s Web, Inc. (July 2021), available at FDA, 75-Day Premarket Notification for New Dietary Ingredients 2021, Docket No. FDA-2021-S-0023-0053, https://www.regulations.gov/document/FDA-2021-S-0023-0053; Letter from Cara Welch, Ph.D., Acting Director, Office of Dietary Supplement Programs, CFSAN, to Irwin Naturals (July 2021), available at FDA, NDI 1199 – Full-Spectrum Hemp Extract (FSHE) from Irwin Naturals, Docket No. FDA-2021-S-0023-0050, https://www.regulations.gov/document/FDA-2021-S-0023-0050.

9. Id.

10. See FDA Voices, Stephen Hahn, M.D., FDA Commissioner, and Amy Abernathy M.D., Ph.D., FDA Principal Deputy Commissioner, “Better Data for a Better Understanding of the Use and Safety Profile of Cannabidiol (CBD) Products,” (January 2021), available at https://www.fda.gov/news-events/fda-voices/better-data-better-understanding-use-and-safety-profile-cannabidiol-cbd-products.

11. See supra, n.4

12. Id.

13. FDA News & Events, “Cannabis-Derived Products Data Acceleration Plan,” (October 2021), available at https://www.fda.gov/newsevents/public-health-focus/cannabis-derived-products-data-acceleration-plan.

14. Id.

15. See FDA Webpage, “FDA Regulation of Cannabis and Cannabis-Derived Products, Including Cannabidiol (CBD) – FDA Communications,” available at https://www.fda.gov/news-events/public-health-focus/fda-regulation-cannabis-and-cannabis-derivedproducts-including-cannabidiol-cbd#fdacomm.

16. See supra, n.4

17. FDA Constituent Update, “FDA Warns Companies for Illegally Selling Food and Beverage Products that Contain CBD,” (November 2022), available at https://www.fda.gov/food/cfsan-constituent-updates/fda-warns-companies-illegally-selling-food-and-beverageproducts-contain-cbd.

18. FDA News Release, “FDA Issues Warning Letters to Companies Illegally Selling CBD and Delta-8 THC Products,” (May 2022), available at https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-issues-warning-letters-companies-illegally-selling-cbd-anddelta-8-thc-products.

19. FDA Statement, “FDA Concludes that Existing Regulatory Frameworks for Foods and Supplements are Not Appropriate for Cannabidiol, Will work with Congress on a New Way Forward,” (January 2023), available at https://www.fda.gov/news-events/pressannouncements/fda-concludes-existing-regulatory-frameworks-foods-and-supplements-are-not-appropriate-cannabidiols.

20. White House Briefing Room, “Statement from President Biden on Marijuana Reform,” (October 2022), available at https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2022/10/06/statement-from-president-biden-on-marijuana-reform/.

21. See Marijuana Moment, “Biden Will Sign Bipartisan Marijuana Research Bill Passed by Congress This Week, White House Says,” (November 2022), available at https://www.marijuanamoment.net/biden-will-sign-bipartisan-marijuana-research-bill-passed-bycongress-this-week-white-house-says/.

22. AAP, “Pediatric Edible Cannabis Exposures and Acute Toxicity: 2017-2021,” (January 2023), available at https://publications.aap.org/pediatrics/article/doi/10.1542/peds.2022-057761/190427/Pediatric-Edible-Cannabis-Exposures-and-Acute?autologincheck=redirected; See also, WaPo, Elizabeth Chang, “Steep increase of kids accidentally eating cannabis edibles, data shows,” (January 2023), available at https://www.washingtonpost.com/parenting/2023/01/03/edibles-kids-increasing/.